Sent to you by moya via Google Reader:

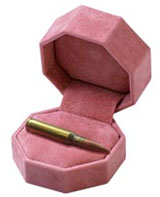

It's holiday season. Often, this time of year, people feel romantic. Consequently, engagements and gifts of jewelry abound. Having many people in my life become engaged and married of late, I've been thinking a lot about all the bling that goes along with these endeavors.

It's holiday season. Often, this time of year, people feel romantic. Consequently, engagements and gifts of jewelry abound. Having many people in my life become engaged and married of late, I've been thinking a lot about all the bling that goes along with these endeavors.

Specifically, I've been thinking about diamonds. Why, you ask? Well, because as I see more and more friends and family become engaged I have been seeing more and more diamonds. To be clear, I have not become pre-occupied with the idea of engagements and rings, but with the desire for diamonds in particular. I've been trying to understand just what it is that makes them so desirable, given that we all know, on some level, that the market demand for these stones fuels violent conflict, war and suffering in many places of the world. That is the connection that I aim to tease out.

A caveat: I have many friends and family members who own diamonds and covet them. In fact, I, too, find them quite beautiful, as a self-professed lover of shiny, beautiful baubles. I possess one pair of diamond earrings that belonged to my Nani (grandmother) in India and were given to me by mother after Nani passed. I love those earrings, and wear them rarely, with a mixture of both sorrow and joy. When I see diamond rings, earrings and necklaces on others, I admire their beauty. Increasingly, though, I find it very hard to un-remember the social ramifications of our cultural desire to give/own/receive diamonds as declarations of love and affection. Especially, when I think of the wars that these beautiful objects make us complicit in.

In specific regard to engagements: others have argued about whether or not they are an outmoded social custom. Quite honestly, I believe in living and letting live on this issue. I'm not here to be the crunk feminist betrothal police. I certainly, have my own opinion about engagements (I'm down) and weddings (it's complicated) and the relation of all these things to romantic love (perhaps a forthcoming blog-post?).

In specific regard to engagements: others have argued about whether or not they are an outmoded social custom. Quite honestly, I believe in living and letting live on this issue. I'm not here to be the crunk feminist betrothal police. I certainly, have my own opinion about engagements (I'm down) and weddings (it's complicated) and the relation of all these things to romantic love (perhaps a forthcoming blog-post?).

A smidgen of history: The "tradition" of the diamond engagement ring is actually rather new. The first known diamond engagement ring was commissioned for Mary of Burgundy by the Archduke Maximilian of Austria in 1477. Then, in the late 19th century, mines were discovered in South Africa, driving down the price of diamonds. After which, Americans regularly began to give (or receive) diamond engagement rings. Before this moment, some women got thimbles instead of rings to signal their betrothal.

Now here's the clincher (from a great piece by Meghan O'Rourke in Slate):

"Even then, the real blingfest didn't get going until the 1930s, when—dim the lights, strike up the violins, and cue entrance—the De Beers diamond company decided it was time to take action against the American public.

In 1919, De Beers experienced a drop in diamond sales that lasted for two decades. So in the 1930s it turned to the firm N.W. Ayer to devise a national advertising campaign—still relatively rare at the time—to promote its diamonds. Ayer convinced Hollywood actresses to wear diamond rings in public, and, according to Edward Jay Epstein in The Rise and Fall of the Diamond, encouraged fashion designers to discuss the new "trend" toward diamond rings. Between 1938 and 1941, diamond sales went up 55 percent. By 1945 an average bride, one source reported, wore "a brilliant diamond engagement ring and a wedding ring to match in design." The capstone to it all came in 1947, when Frances Gerety—a female copywriter, who, as it happened, never married—wrote the line "A Diamond Is Forever." The company blazoned it over the image of happy young newlyweds on their honeymoon. The sale of diamond engagement rings continued to rise in the 1950s, and the marriage between romance and commerce that would characterize the American wedding for the next half-century was cemented. By 1965, 80 percent of American women had diamond engagement rings."

[For an interesting demonstration of cultural production, please see the DeBeer's Website for their version of the history of the engagement ring.]

So, in light of all this, let's return to the central question: what exactly is a conflict diamond?

"Conflict diamonds are diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council."

According to the NGO, Global Witness, conflict diamonds have funded brutal conflicts in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo and Côte d'Ivoire. These conflicts have resulted in the death and displacement of millions of people. Diamonds have also been used by terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda to finance their activities and for money-laundering purposes.

Brought into the mainstream by the film Blood Diamond, which featured Hollywood heavyweights like Leonardo DiCaprio, Djimon Hounsou and Jennifer Connelly, there has been some attention drawn to conflict diamonds and the long standing movement to curb and eliminate their production.

In 1998, Global Witness (which was co-nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for this work) launched a campaign to expose the role of diamonds in funding conflict, as part of broader research into the link between natural resources and conflict. In response to growing international pressure from such NGOs, the major diamond trading and producing countries, representatives of the diamond industry, and NGOs met in Kimberley, South Africa to determine how to tackle the blood diamond problem. The meeting, hosted by the South African government, was the start of a complicated and fraught three-year negotiating process, which culminated in the establishment of an international diamond certification scheme. The Kimberley Process was launched in 2003, and endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council. According to NGO's like Global Witness, who are monitoring and evaluating the Kimberly Process it's clear that diamonds are still fueling violence and human rights abuses. Although the Process makes it more difficult for diamonds from rebel-held areas to reach international markets, there are still significant weaknesses in the scheme that undermine its effectiveness and allow the trade in blood diamonds to continue.

Knowing this, here's why I decided to research and write this post: we can actually stop this. Diamonds are not food. Diamonds are not required for survival. A change in cultural attitudes can actually stop these conflicts. It can stop the violence in communities where these diamonds are found. If the desire for diamonds were to vanish, these conflicts would lose exactly what fuels them.

I don't write this post to make people with diamonds on their fingers feel bad. I shop for bargain goods that I know are made in sweatshops. When I purchase produce, I know that it was grown and picked by laborers whose rights are violated. I try to make ethical choices, all while knowing that I am complicit in a world economy that is rooted in human rights violations.

This is the beautiful thing about symbols, they can be changed. They have only as much power as we give them. We can actually stop much, if not all, of the violence that is a result of the demand for diamonds. They way that our cultural attitudes about buying fur have changed within a generation, so can our cultural attitudes about diamonds, I propose. It's not really going to be easy, they are a beautiful and powerful symbol of wealth and status. Increasingly, I hear many politically conscious people say they want a "vintage" diamond. This is clearly an effort towards detangling oneself from the trade of conflict diamonds. My point here, though, is about the cultural cache of diamonds. While purchasing a vintage one might not support the blood diamond industry directly, it certainly does nothing to challenge the value that diamonds have in our society.

All that being said, I think we can indeed move the needle.

"Diamonds are forever" it is often said. But lives are not. We must spare people the ordeal of war, mutilations and death for the sake of conflict diamonds." – Martin Chungong Ayafor, Chairman of the Sierra Leone Panel of Experts

However, eventually, I think we can change the way we think about diamonds. If we know more, and if we are challenged to face the truth about the havoc they wreak, we might make different choices. We might not choose diamonds after all. They have nothing to do with love, as it turns out.

Things you can do from here:

- Subscribe to The Crunk Feminist Collective using Google Reader

- Get started using Google Reader to easily keep up with all your favorite sites

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment