Sent to you by moya via Google Reader:

Today is Frida Kahlo's birthday. In honor of her and her work, I took time to sit, breathe and reflect on Frida and all that her work has meant to me. I often think about Frida and what it means to recognize each other, as disabled queer women of color. I don't know if Frida would have described herself as "disabled;" if she would have even used that language, that thinking. Would she have thought of herself as what we understand as "queer," using whatever language and words she chose around her open bisexuality? I don't know.

Today is Frida Kahlo's birthday. In honor of her and her work, I took time to sit, breathe and reflect on Frida and all that her work has meant to me. I often think about Frida and what it means to recognize each other, as disabled queer women of color. I don't know if Frida would have described herself as "disabled;" if she would have even used that language, that thinking. Would she have thought of herself as what we understand as "queer," using whatever language and words she chose around her open bisexuality? I don't know.

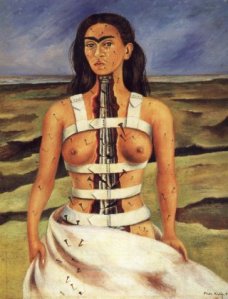

I found Frida when I was young, and it seems I have been continuing to find her my whole life. Frida was originally introduced to me when I was a young teenager as a feminist symbol; as a "strong woman of color artist." As one of the few non-black woman of color thrown in amongst majority white women, I remembered her. It was only later that I found out she, like me, had polio as a child and about her bisexuality. For me, Frida was a symbol of one of the few disabled queer women of color that I knew of. Her paintings conveyed things beyond words about bodies, death and pain at a time before I had the tools and language with which to talk about disability, surgeries, legs, spines, backs, pain, womanhood, suicide, shame, desire and self-hate. She was a necessary reflection of parts of me when I felt so alone, cut-off, isolated and like a freak. Her paintings were some of the only visual images of disabled women of color that I had, period. And the fact that she was painting herself and deciding how she wanted to be seen and understood was even more powerful.

Frida helped me to recognize pieces of myself and for that I will forever be grateful.

To me, Frida was descriptively disabled and queer, even though she may (or may not) have (politically) identified as such or used that language. When I say "descriptively disabled", I mean someone who has the lived experience of being disabled. They may not talk about ableism, discrimination or even call them selves "disabled," but they know what it feels like to be in a wheelchair, experience chronic pain, have people stare at you, walk with a brace, be isolated, etc. There are many people who are descriptively disabled who never become or identify as "politically disabled." When I say "politically disabled," I mean someone who is descriptively disabled and has a political understanding about that lived experience. I mean someone who has an analysis about ableism, power, privilege, who feels connected to and is in solidarity with other disabled people (regardless of whatever language you use). I mean someone who thinks of disability as a political identity/experience, grounded in their descriptive lived experience. (The same is true for descriptively queer, descriptively woman of color, descriptively adoptee and so on.) I don't know if Frida was politically disabled or queer.

This distinction is helpful for me, because the majority of the disabled women of color (especially queer women of color) I meet are descriptively disabled, as was I for a long time. Or they are descriptively queer.

Though it is hard, it makes sense to me because the risks of being a political queer disabled woman of color are great. The risk of more isolation, more stigma, more annoyance ("You're bringing that up again??"), more visible-invisibility can be too much to even consider. The risk of being yet another woman of color who is thought of as "too much." I meet queer women of color who are descriptively disabled, but have enormous resistance to thinking of themselves as disabled. Narratives of "independence," "miracle," and "super crip" abound or the cost of being a political woman of color is too high and survival as a disabled person depends on not connecting their disability with their race…or queerness. (And the cold, hard truth is that there is just as much ableism in within queer communities as there is with straight communities—don't be fooled.)

Though it is hard, it makes sense to me because the risks of being a political queer disabled woman of color are great. The risk of more isolation, more stigma, more annoyance ("You're bringing that up again??"), more visible-invisibility can be too much to even consider. The risk of being yet another woman of color who is thought of as "too much." I meet queer women of color who are descriptively disabled, but have enormous resistance to thinking of themselves as disabled. Narratives of "independence," "miracle," and "super crip" abound or the cost of being a political woman of color is too high and survival as a disabled person depends on not connecting their disability with their race…or queerness. (And the cold, hard truth is that there is just as much ableism in within queer communities as there is with straight communities—don't be fooled.)

The risk of having to begin to have conversations about ableism, access and power in our families, with our caregivers, attendants, co-workers, friends and lovers is tremendous, often times threatening the very delicate web of access we've managed to create—threatening our very survival. How do you talk about queerness when it is assumed you have no sexuality as a disabled person, while simultaneously you are washed with racist gender stereotypes about women of color's desire and sexuality? What does it mean to be stripped of our sexuality at the same time we are hypersexualized at the same time that we are infantilized at the same time that it is assumed we will shoulder the brunt of the work? There is great risk in visibility.

And even when we are visible as disabled queer women of color, sometimes we don't even recognize each other. We don't recognize each other because we're not taught how to do it; because we're taught how to be afraid of each other. Because we are taught how to not recognize each other more readily than we are taught how to find each other. Where are we? How do we find each other? And how do we do the work to recognize each other and to be recognizable to each other? Sometimes, as is so often the case with queerness (and disability), I see you, but I don't know if you see me. I feel this acutely with adoptees. We share space together, but often times we don't know how to recognize each other. We look right through one another, or avoid each other as if we were taught some kind of secret script.

I wonder about Frida and my recognition of her and if she would have recognized me.

I want you to recognize me. And I want to leave evidence about how I made myself recognizable to you (for you) and about how I tried to find you—to make it easier for the next time we are faced with ourselves/each other. Because there were so many times I chose not to recognize myself inside of me as well—there were times I avoided myself.

We can learn how to recognize each other. We can teach each other. We must practice recognizing each other. And we need as many visible queer disabled women of color as possible to help us get there. As many of us who are living our lives and are able to leave trails and stories about the way we felt, looked, moved, survived and created. As many of us who refuse to let our disabled queer struggles get subsumed by the able bodied queer movement as only queer; who refuse to let our disabled people of color stories get subsumed by the white disability movement as only disabled; who refuse to be invisible, for the sake of each other. As many of us who are cultivating the elder in us all to be here (in whatever way we can) for those who come after us, because they will need us.

So, today, on Frida Kahlo's birthday, I sit in gratitude for her paintings. They were an avenue of recognition for me. They were a way for me to recognize pieces of her, and in turn, a way to recognize pieces of my self, and allow me to recognize others. I thank her for her life and her honesty and all of the complexities she holds. Thank you.

"I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best." –Frida Kahlo

"I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best." –Frida Kahlo

Things you can do from here:

- Subscribe to Leaving Evidence » Reflecting on Frida Kahlo’s Birthday and The Importance of Recognizing Ourselves for (in) Each Other using Google Reader

- Get started using Google Reader to easily keep up with all your favorite sites

.jpg)

2 comments:

I loved reading this piece. Frida is an inspiration!

I also have a question for you: do you believe it is possible to be politically disabled and not descriptively disabled at the same time?

hi hilden, no, i don't think you can be politically disabled without being descriptively disabled. In the way that i am using, it is very important that politically disabled folks' political understanding of disability be grounded in their lived experience of being descriptively disabled (even if they don't identify as "disabled").

I think for folks who are non-disabled (not descriptively disabled) it could be useful to have a different word to describe them. there are a lot of comrades who are working to confront their ableism/ableist privilege, trying to be in support of disabled folks and communities and figuring out what solidarity looks like. This is very important. We need this. but of course whenever privilege folks begin to examine their privilege and start to learn about a lived experience that they do not share, there is always the risk of able-bodied/temporarily able bodied people feeling entitled or authorized (and being empowered) to speak about, on behalf of the very people that their privilege works to oppress. Disabled people (like all oppressed groups) have a long history of able-bodied folks speaking for us, defining our lives, and exploiting us. Right now, we have the phenomenon where disability politics are actually becoming (or on the edge of becoming) trendy, so you have places where disability is being talked about, but there are no descriptively disabled people present. Or you have non-disabled people being asked to speak about disability or feeling entitled to disabled-only spaces.

This is why it is so important for politically disabled people to be descriptively disabled because it is so important that we speak for ourselves and that comrades do the work of being in solidarity, taking lead from us, stepping back and most importantly, working with other able-bodied folks on their ableism, calling ableism out when it happens and doing their own work of confronting their ableism.

My opinion. I hope this helps!

Post a Comment