Sent to you by moya via Google Reader:

"Number 47 looks like my second-grade teacher. Number 83 resembles one of my daughters. Number 66 calls to mind my children's grandmother. And although some faces were cropped from near-naked bodies, others were shot outdoors, wearing boots and jackets," said LA Times Reporter, Sandy Banks, commenting on photos of unidentified Black females.

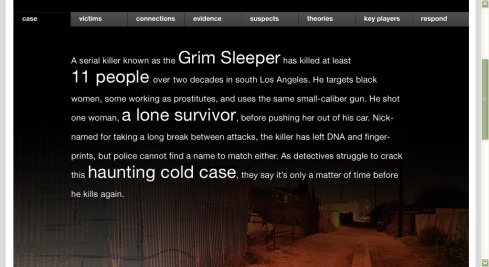

Debra Jackson. Click. Henrietta Wright. Click. Barbara Ware. Click. These are some names of Black women who were sexually assaulted, drugged, murdered, and dumped in LA alleys and the backstreets by a former city trash collector. As news broke about a serial killer dubbed the Grim Sleeper, I found myself at the computer clicking on the still images of 180 nameless, numbered Black women and girls published by the LA Times. I sat with each photo picturing each life—and remembering the life of my aunt who was murdered years ago.

Debra Jackson. Click. Henrietta Wright. Click. Barbara Ware. Click. These are some names of Black women who were sexually assaulted, drugged, murdered, and dumped in LA alleys and the backstreets by a former city trash collector. As news broke about a serial killer dubbed the Grim Sleeper, I found myself at the computer clicking on the still images of 180 nameless, numbered Black women and girls published by the LA Times. I sat with each photo picturing each life—and remembering the life of my aunt who was murdered years ago.

For women who are poor, who are Black, who are substance abusers, who are single/mothers, who are sex workers, and for women who possess no Olan Mills yearbook portrait like that of Natalee Holloway, how do we make sense of their lives? Do we see them?

The national news coverage of the 1985-2007 LA murders has been sensational. It has created a weeklong media event where images of rape survivors, recovering addicts, missing persons, family friends and kinfolk serve as a collective spectacle to construct a gritty drama about Lonnie Franklin Jr., the accused killer cast as the Grim Sleeper. The first LA Times web photo of an unidentified Black woman, for example, included a star rating. (The star rating, 3 out of 5, has been removed from the photo and women who've confirmed their identity with the LAPD have had their photos removed from the site.) Also, the CNN website mirrors entertainment pages for television crime series, such as CSI. The opening page resembles a movie trailer.

Buried beneath the news headlines and hidden between police press releases is the actual story: The Black male serial killer. I am unsure if the media public is appalled by the dead Black women as we are fascinated by Franklin because he represents the methodicalness assigned to white male serial killers.

The Franklin case prompted me to think about other news stories reporting updates or new cases in 2010 about serial murderers, Walter Ellis and Jason Thomas Scott, who targeted Black women and girls in Wisconsin and Maryland.

You would think the separate news stories about the systematic killing of Black women and girls in different regions would launch a national conversation about gender violence in Black communities. In the same week that a major network news station reported the LA murders, it also celebrated the No. 1 YouTube video called "Bed Intruder." The video has been watched more than 54 million times. It uses actual news footage of Antonio Dodson, a concerned brother who reports on the attempted rape of his sister Kelly. I remain dumbfounded by the complete thematic disconnect and the utter disregard for the actual loss of Black girls and women. It is as if media makers and the consuming public are unable to see Black women unless we are repackaged as entertainment.

I began thinking about this piece yesterday. I imagined there were other stories to tell that would not sour our holiday eggnog. Then, I listened to the interview by Stephanie Jones, who created MOMS (Missing Or Murdered Sisters) to raise money and national awareness about the serial murders of poor Black women in Rocky Mount (NC). She had to rent a billboard to  attract local media attention. But after watching the morning news about another serial murderer yesterday, I could not look away. At a press conference Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter announced a $37,000 reward (from the city and police fraternal organizations) for the arrest of a Black man accused of killing three non-Black female sex workers. The news coverage about Philadelphia's "Kensington Strangler" brought it all home. My aunt, Mildred Darlene Durham, lay dead from gunshot wounds in the Kensington area of Norfolk (VA) in 1998.

attract local media attention. But after watching the morning news about another serial murderer yesterday, I could not look away. At a press conference Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter announced a $37,000 reward (from the city and police fraternal organizations) for the arrest of a Black man accused of killing three non-Black female sex workers. The news coverage about Philadelphia's "Kensington Strangler" brought it all home. My aunt, Mildred Darlene Durham, lay dead from gunshot wounds in the Kensington area of Norfolk (VA) in 1998.

At end of group sessions, Black feminist Ruth Nicole Brown used to invite me and other members from an Illinois collective called SOLHOT (Saving Our Lives, Hearing Our Truths) to light an incense to recall another person or to remember ourselves. We stood face to face so that we might see each other. One by one, we would say the names of a loved one so she/we would not be forgotten.

This is my virtual incense to Darlene and every other Black woman whose face has been etched in my memory.

I do see you. You have not been forgotten.

You are loved. You are missed.

Things you can do from here:

- Subscribe to The Crunk Feminist Collective » Do we need a body count to count?: Notes on the serial murders of Black women using Google Reader

- Get started using Google Reader to easily keep up with all your favorite sites

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment