There have been several public "events" privileging race, gender, and class during the past weeks in New York City that featured prominent Black feminists. After the film screening of The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975, the conference about Anita Hill 20 Years Later: Sex, Power and Speaking the Truth, and the Occupy Wall Street movement based in Zucotti Park/Liberty Square, I wanted to mark how Black womanhood and Black feminist thought are positioned.

The Black Power Mixtape, 1967-1975

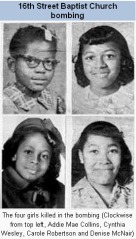

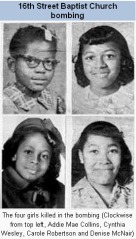

The Swedish film is an incredible compilation or mixtape that chronicles the US Black freedom movement by arranging interviews, speeches, and snapshots of activists and urban Black life. The most compelling moments include Black women. There is one scene, for example, when Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) sits on an apartment floor boyishly looking up at his mother Mable. In a "play" interview, he presses her to describe the intersections between race and class. It is a humorous, affectionate exchange that complements the defiant image of Carmichael championing Black power. Carmichael's fiery rhetoric at the beginning is matched by Angela Davis' cool midway through the film when she responds to a question about armed resistance. Davis recalls the 1963 Birmingham church bombings when

1963 Birmingham Klan bombing that killed four Black girls

neighborhood girls Addie Mae, Cynthia, Carole and Denise were brutally murdered by white supremacists. She places her personal recollection within a context of ongoing racial terrorism experienced by African descended people. In one story Davis reveals American hypocrisy. In one story she creates an emotional bridge to connect with the film so the audience could better understand the complexities of Black America then and now. (The CFs in the audience echoed, "that's Black feminism for you.")

The Davis and Carmichael interviews are followed by a third moment, which is the most unsettling part of the film because I am left hanging, wondering what to do with a local teary-eyed young Black woman who describes how she has had to wrestle with her drug addiction after a family member sexually assaults her as a child. In the midst of the Black power movement, we are invited to read her story as part of "the ghetto" and hear the PSA-like radio voice-over about premature babies from drug-addicted mothers as hers. The film explains drug abuse by Black male Vietnam veterans who return home disillusioned, homeless and unemployed, and it illustrates gender-specific forms of (sexual) violence experienced by Black men who are tortured during the Attica uprising, but there is no commentary, no gender framework to really see her or other dazed Black women shooting up in an abandoned New York apartment. In fact, if we are to gather any meaning at all from the voice-over, street footage, and her interview, we might believe that she has failed her family and by extension the Black community—ideas echoed by the news media a decade later when audiences are re-introduced to the bad Black woman as the crack-welfare-mother. That the director-editor, Goran Hugo Olsson, opted to let saturated images of the ghetto "speak for itself" while admittedly letting go of the archived footage of the landmark 1972 Presidential Candidate, Shirley Chisolm, suggests specific discussions about gender added an unwanted complexity to the Black power he envisioned.

Anita Hill 20 Years Later: Sex, Power and Speaking the Truth

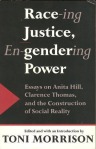

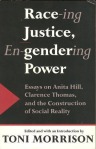

The daylong conference began with sessions about Anita Hill's 1991 testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee during the confirmation hearings of then US Supreme Court nominee, Clarence Thomas. The Sex and Justice film excerpt and morning sessions were followed by lunch discussions about sexual harassment in the military, on the streets, and in schools, and a keynote about home with Hill herself. Hill asked (and I paraphrase), "Is there a way to  talk about race that isn't so male dominated?" Hours before Hill posed this question I asked myself, is it possible to talk about gender on a national scale that isn't so white identified? I had come to the conference to learn more about Hill specifically and about Black feminist thought in general (as the tag was "an all day conference about race and gender identity"). I got it even though it felt sandwiched between a kind of deracialized gender, which eclipsed the intersectionality so many women of color emphasized. Long before Kimberlé Crenshaw reminded us about intraracial resistance to Hill and other Black women who dared to air dirty laundry, and before Melissa Harris Perry offered us her exacting critique about respectability and the reception of The Help, a New York college instructor leaned over to school the Black-girl-too-young-to-remember about the Thomas-Hill hearings. Pulling out her Black feminist good book, Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power, my informal Black feminist instructor suggested Hill had been embraced by white feminists because Thomas seemed less threatening to their social standing than the white men who systematically harassed Black women in the workplace. From my back-seat instructor to the panelists on stage, it would appear the symbolic body of Hill was still very much in the making. At the daylong conference, Hill stood (in) as a testament to interracial feminist solidarity, "front line" Black feminist mobilization, and white feminist cooptation (for at least one sistah in the audience).

talk about race that isn't so male dominated?" Hours before Hill posed this question I asked myself, is it possible to talk about gender on a national scale that isn't so white identified? I had come to the conference to learn more about Hill specifically and about Black feminist thought in general (as the tag was "an all day conference about race and gender identity"). I got it even though it felt sandwiched between a kind of deracialized gender, which eclipsed the intersectionality so many women of color emphasized. Long before Kimberlé Crenshaw reminded us about intraracial resistance to Hill and other Black women who dared to air dirty laundry, and before Melissa Harris Perry offered us her exacting critique about respectability and the reception of The Help, a New York college instructor leaned over to school the Black-girl-too-young-to-remember about the Thomas-Hill hearings. Pulling out her Black feminist good book, Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power, my informal Black feminist instructor suggested Hill had been embraced by white feminists because Thomas seemed less threatening to their social standing than the white men who systematically harassed Black women in the workplace. From my back-seat instructor to the panelists on stage, it would appear the symbolic body of Hill was still very much in the making. At the daylong conference, Hill stood (in) as a testament to interracial feminist solidarity, "front line" Black feminist mobilization, and white feminist cooptation (for at least one sistah in the audience).

Occupy Wall Street

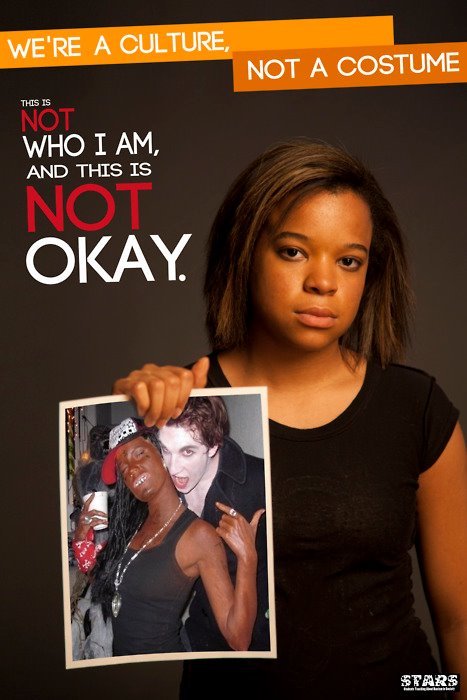

Occupy Wall Street has been characterized as white middle class rage against the capitalist machine. Prior to the Harlem march where folks from Liberty Park joined activists of color to protest the stop-and-frisk policies that disproportionately targeted Black and Latino persons, communities of color insisted the "occupiers" reconsider language (e.g., replace occupy to decolonize) and reconsider tactics, such as voluntarily camping in spaces that displaced homeless persons. The first time I went to Liberty Park, Black folks peppered the space. We were mainly on the margins, taking up space on the steps and the stone parameters of the blue tarp makeshift community.

The physical make up of the protestors at the Park and on the street during the Manhattan marches appeared to be the same, yet the meetings and talks I attended attempted to be inclusive and intentionally anti-racist even in the absence of a lot of colored folk. (See Greg Tate's Top 10 Reasons Why So Few Black Folks Appear Down to Occupy Wall Street.) And just like I stayed at the Hill conference, I came back to Liberty Park because I wanted to hear an amazing Black intellectual, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, explain capitalism's connection to group exclusion, criminalization, and racialized labor.  When Gilmore evoked CLR James, she reminded me of another Trinidadian thinker, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), that I had seen weeks earlier in the Black Power Mixtape. Immediately after Gilmore's talk, I walked upstairs to see a remarkable scene for which I still have no meaning. To my left, Rev. Jesse Jackson was surrounded by a small group of men with studio cameras and a spotlight. To my right, the actor Rev. Billy began his popular street performance as the crowd circled. Onlookers held up camera phones to record the spectacle of the Black-led choir and the Reverend, who dramatically preached about the evils of consumerism. Each had a platform at Liberty Square to talk about economic justice, however, their messages were digested and distributed differently. Jesse was on my left, Billy was on the right, and Ruth (or Ruthie if you know her) was somewhere in between…

When Gilmore evoked CLR James, she reminded me of another Trinidadian thinker, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), that I had seen weeks earlier in the Black Power Mixtape. Immediately after Gilmore's talk, I walked upstairs to see a remarkable scene for which I still have no meaning. To my left, Rev. Jesse Jackson was surrounded by a small group of men with studio cameras and a spotlight. To my right, the actor Rev. Billy began his popular street performance as the crowd circled. Onlookers held up camera phones to record the spectacle of the Black-led choir and the Reverend, who dramatically preached about the evils of consumerism. Each had a platform at Liberty Square to talk about economic justice, however, their messages were digested and distributed differently. Jesse was on my left, Billy was on the right, and Ruth (or Ruthie if you know her) was somewhere in between…

.jpg)